Good Grief: Honoring Loss

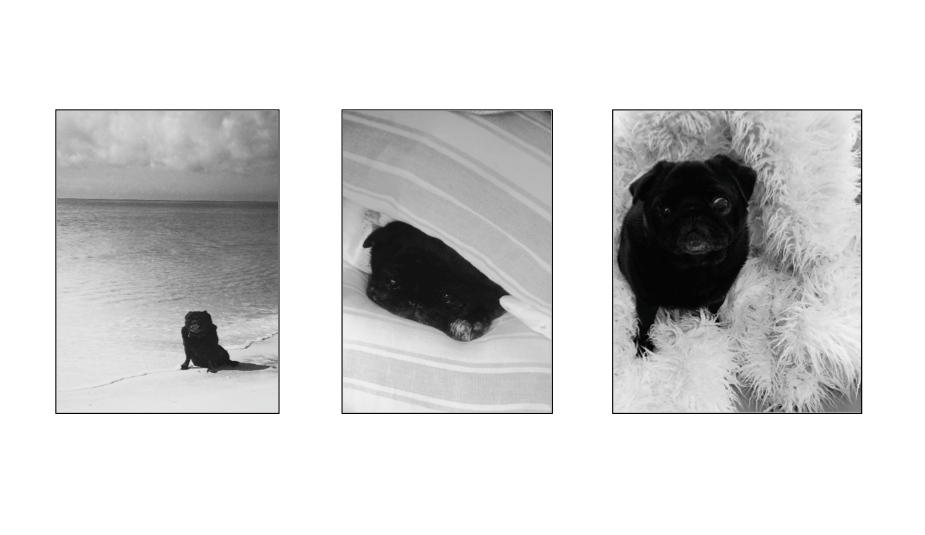

“Rugby”

Have you ever attended a funeral for a goldfish? To some this may sound like an odd question but consider this: as young children, many of us didn’t think twice about whether or not our loss was significant enough to warrant grieving. We didn’t judge our sadness. We were simply sad and most likely cried if we lost something we cared deeply for and loved.

Recently in my own life, our dog, Rugby died unexpectedly. I took him to the vet to get some teeth pulled and not long after he was gone.

I’ve spent several sessions of my own therapy now talking about the death of our dog. I feel guilty when I start to think about how I might have prevented his death and start wishing I could do impossible things like go back in time and take him back to the vet when I felt something was “off”.

I also feel shame when I think about how sad I feel and still feel about losing him. As I continue to process my feelings I keep waiting for the gift of acceptance that is supposed to come from feeling my sadness, but it hasn’t arrived yet.

These are all healthy reactions to loss and yet in my humanness, even I want an end date for my sadness and judge how it hasn’t come yet. I’ve also judged the intensity of my feelings and continue to wonder how an animal has left a bigger hole in my heart than many of the humans I’ve lost in my life.

Grief is not exclusive to just death of persons or pets though. To be human is to experience loss. Simply being alive means endless possibility for grieving in a multitude of ways. The loss of health, innocence, safety, jobs, faith, or relationship for example all carry their own unique impact and are worthy of acknowledging and processing if needed.

And while there is no exact formula to the process of grieving I have found these things to be true:

1. The deeper we value something or someone, the greater the sadness we experience when we lose it/them.

2. We cannot control when or how sadness shows up.

3. We have a choice of how we respond to sadness: stuff it or engage it.

4. Grieving alone is good, but there also seems to be a greater healing power in sharing our sadness in the context of relationship with others.

5. Our experience of loss is connected to our story.

How Can Therapy Help?

As well-known grief counselor Steve Levin writes, “it is the surrender of resistance that opens pain to healing” (p. 19 Unattended Sorrow). Leaning into loss is actually what softens its edges while actively pushing it away often sharpens them, giving unattended sorrows even greater power to affect us in less desirable ways.

Therapy is a space to explore your personal experience of loss in the context of a safe relationship and without judgment. In therapy the importance does not lie in an outsider’s perceived value of a loss, but rather the experience of the one who is grieving and how this affects your present reality.

If you need a safe place to sift through your own experiences of loss, reach out.